Allow me to borrow your imagination for a minute.

Imagine that you constantly feel as though you’re carrying a dull, heavy ache in your pelvis, in addition to frequent migraines, nausea, and fatigue. Imagine having to ‘write off’ at least 2 weeks out of the month; rescheduling plans and calling in sick to work, because you know you’re not going to be well. Imagine feeling as though you’re being zapped with powerful electric shocks that start in your abdomen/pelvic region, and spread throughout your body, forcing you to stop whatever you were doing. You spend hours writhing, trying to find a position that makes the pain easier to tolerate while you wait for your painkillers to kick in, but nothing is comfortable. Imagine feeling pain so intense, that it turns your vision black while your eyes are still open. Imagine waking up in the middle of the night and not being able to go back to sleep, until the pain makes you lose consciousness.

Yikes!

To make things worse, whenever you go to the doctor, they tell you that you’re in good health because all of your scans and tests come back normal. After years of trying, you finally manage to find a doctor who agrees that you shouldn’t suffer like this and allows you to undergo surgery to investigate. After the surgery, you are told by the surgeon that you have ‘mild’ endometriosis, and you are told to take contraceptive hormones. The pain improves ever so slightly, but it never completely goes away.

Now, imagine someone who doesn’t feel any of those symptoms described above. They have only recently begun to feel a small amount of pressure in their pelvis, which makes it uncomfortable to sit down for too long. They go to the doctor, who requests a scan for them. The scan reveals a 7cm growth that will need to be surgically removed. After the surgery, they are told that they have ‘severe’ endometriosis that has spread to various organs in their abdomen, and they are told to take contraceptive hormones.

Between those two scenarios, would you have guessed that the latter would be the only one to have severe endometriosis?

Doesn’t really make sense, does it?

How is endometriosis staging done?

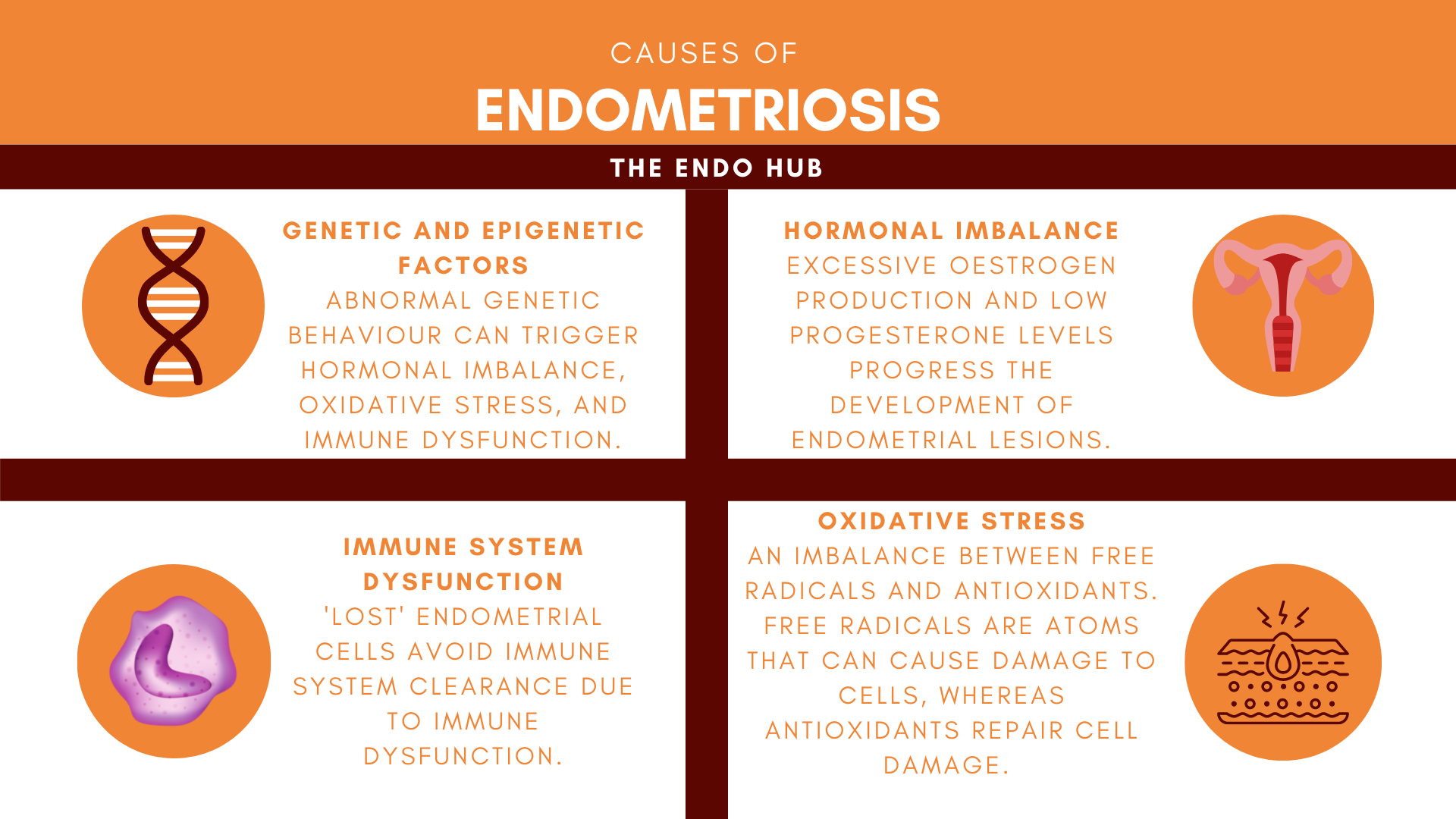

Endometriosis staging is done based on the location and size of the lesions. A study that assessed the correlation between the lesion type, pain severity, and endometriosis stage of over 1000 endometriosis patients, showed there is only a small link between painful periods, non-period pain, and disease severity. The link between staging and disease severity is further complicated by the portion of patients who are asymptomatic. Not only do endometriosis patients have to deal with a confusing disease, but also, a staging system that doesn’t correlate to their symptoms.

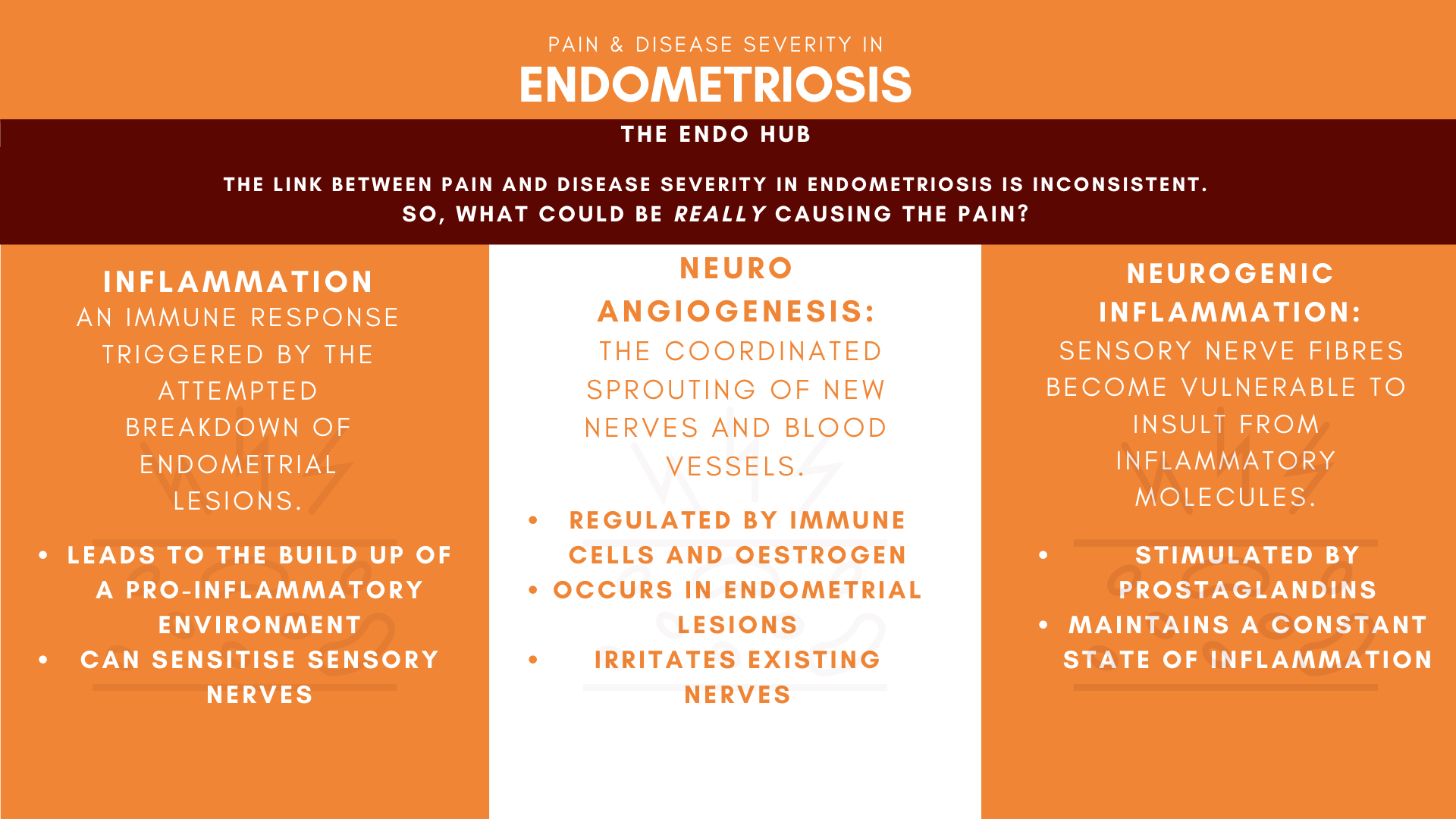

If disease severity and pain in endometriosis are poorly correlated, what could be the cause of the chronic pain observed in endometriosis? Scientific studies have often linked endometriosis pain with endometrial lesions or scarring from surgical procedures. Although these can be a trigger for endo-related pain, they are not the only possible causes.

Keep on reading to find out the possible causes of chronic pain in endometriosis.

How do we feel pain?

Everyone has a different threshold for how much pain they can tolerate- something that is very painful for you might not be very painful for someone else, making it a very personal experience.

Pain is defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) as “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with because of actual or potential tissue damage.”

Take a look at the infographic below to learn about how the body processes pain:

Inflammation

Inflammation is a natural process within the body that works to fight cell damage. When cells are injured, the immune system strikes back by sending chemicals called ‘inflammatory mediators’ to the location of the injury, beginning the healing process.

During a period, the lining of the uterus breaks down, causing bleeding. This is controlled by a range of immune system cells, and also a drop in levels of oestrogen and progesterone. The immune cells involved also release byproducts such as iron and prostaglandins to complete this process, which can become harmful when they become too much. Prostaglandins are released as part of the inflammatory response to reduce pain, but they can also cause pain. Weird, right?

Inflammation at lesion sites and within the tissue that lines the abdomen and pelvis (peritoneal cavity) can change the way pain is processed in the brain. This is a possible cause of chronic pain in endometriosis. The attempted breakdown of endometrial lesions expressing oestrogen and other byproducts triggers an inflammatory response and creates a build-up of a toxic environment where excessive amounts of byproducts thrive. These inflammatory process byproducts have been found to be increased in endometriosis patients with chronic pelvic pain, and are also key players in sensory nerve activation, directly influencing pain. The release of these byproducts increases the immune response, causing the sensory nerves to be more sensitive than normal.

Growth of new nerves and blood vessels

Neuroangiogenesis happens when new nerves and blood vessels grow at the same time. This process is regulated by oestrogen and immune cells such as macrophages, which release proteins that are responsible for the sprouting of new nerves; stimulation of new blood vessels, and inducing pain in existing sensory nerves. Endometrial lesions have been found to undergo neuroangiogenesis as studies have shown elevated levels of these proteins in endometriosis patients. Studies have also revealed an increase in small c-fibre nerve density in the tissue that lines the abdomen and pelvis of endometriosis patients. C-fibre nerves are linked to slow, deep and dull pain, often described by endometriosis patients. Some good news, though, is that the early removal of endometrial lesions may potentially reverse pain hypersensitivity.

In addition to creating new nerves and blood supplies, neuroangiogenesis also facilitates pain by treading on the toes of existing nerves. If endometrial lesions and pelvic nerves are too close together, nerve compression can occur and worsen chronic pelvic pain. Studies have shown endometriosis patients with a higher than normal nerve density exhibit higher pain scores. In short- the more nerves you have, the more pain you can feel!

Neurogenic inflammation: shaking the hornet’s nest

Endometrial lesions leads to a build-up of toxic byproducts, that can make sensory nerves found in endometrial lesions more sensitive than normal. Imagine picking up an angry hornet’s nest (because let’s face it, hornets always seem to be angry) and violently shaking it. The hornets will attack you in response, and if you kill any of them in defence, more hornets will rush to the scene to defend their nest. A similar chain of events occurs in neurogenic inflammation.

Neurogenic inflammation happens when nerves that are more sensitive than normal are irritated. These nerves respond by using cells that release a range of chemicals that maintain a chronic state of neurogenic inflammation. Immune cells called ‘mast cells’ help maintain this toxic environment and have been found to be higher in endometriosis patients. Neurogenic inflammation has also been found to cause chronic pain in conditions such as IBS and Crohn’s Disease.

Endometriosis disease staging needs to change.

Is a staging system that actually correlates to the degree of symptoms endo patients experience, too much to ask? As studies have shown only a small link between pain and disease severity, better staging could lie beyond the lesions. Further research into the toxic environment that endometrial lesions leave in their wake and how this environment impacts the way that pain is processed in the brain, could open up future treatment options and also create a staging system that does not rely on weak links.

References

Anaf, V., El Nakadi, I., De Moor, V., Chapron, C., Pistofidis, G. and Noel, J., 2011. Increased Nerve Density in Deep Infiltrating Endometriotic Nodules. Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation, 71(2), pp.112-117.

Asante, A. and Taylor, R., 2011. Endometriosis: The Role of Neuroangiogenesis. Annual Review of Physiology, 73(1), pp.163-182.

Bacci, M., Capobianco, A., Monno, A., Cottone, L., Di Puppo, F., Camisa, B., Mariani, M., Brignole, C., Ponzoni, M., Ferrari, S., Panina-Bordignon, P., Manfredi, A. and Rovere-Querini, P., 2009. Macrophages Are Alternatively Activated in Patients with Endometriosis and Required for Growth and Vascularization of Lesions in a Mouse Model of Disease. The American Journal of Pathology, 175(2), pp.547-556.

Berbic, M. and Fraser, I., 2013. Immunology of Normal and Abnormal Menstruation. Women’s Health, 9(4), pp.387-395.

Brierley, S. and Linden, D., 2014. Neuroplasticity and dysfunction after gastrointestinal inflammation. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 11(10), pp.611-627.

Chiu, I., von Hehn, C. and Woolf, C., 2012. Neurogenic inflammation and the peripheral nervous system in host defense and immunopathology. Nature Neuroscience, 15(8), pp.1063-1067.

Fauconnier, A. and Chapron, C., 2005. Endometriosis and pelvic pain: epidemiological evidence of the relationship and implications. Human Reproduction Update, 11(6), pp.595-606.

Gibson, D., Collins, F., De Leo, B., Horne, A. and Saunders, P., 2021. Pelvic pain correlates with peritoneal macrophage abundance not endometriosis. Reproduction and Fertility, 2(1), pp.47-57.

Gombert, S., Rhein, M., Winterpacht, A., Münster, T., Hillemacher, T., Leffler, A. and Frieling, H., 2019. Transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 promoter methylation and peripheral pain sensitivity in Crohn’s disease. Clinical Epigenetics, 12(1).

Holzer, P., 2010. Acid sensing by visceral afferent neurones. Acta Physiologica, 201(1), pp.63-75.

IASP, 2020. IASP Announces Revised Definition of Pain – IASP. [online] Iasp-pain.org. [Accessed 23 June 2021].

Laux-Biehlmann, A., d’Hooghe, T. and Zollner, T., 2015. Menstruation pulls the trigger for inflammation and pain in endometriosis. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 36(5), pp.270-276.

Liang, Y., Xie, H., Wu, J., Liu, D. and Yao, S., 2018. Villainous role of estrogen in macrophage-nerve interaction in endometriosis. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology, 16(1).

Maddern, J., Grundy, L., Castro, J. and Brierley, S., 2020. Pain in Endometriosis. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 14.

McAllister, S., Dmitrieva, N. and Berkley, K., 2012. Sprouted Innervation into Uterine Transplants Contributes to the Development of Hyperalgesia in a Rat Model of Endometriosis. PLoS ONE, 7(2), p.e31758.

McAllister, S., Dmitrieva, N. and Berkley, K., 2012. Sprouted Innervation into Uterine Transplants Contributes to the Development of Hyperalgesia in a Rat Model of Endometriosis. PLoS ONE, 7(2), p.e31758.

Mechsner, S., Kaiser, A., Kopf, A., Gericke, C., Ebert, A. and Bartley, J., 2009. A pilot study to evaluate the clinical relevance of endometriosis-associated nerve fibers in peritoneal endometriotic lesions. Fertility and Sterility, 92(6), pp.1856-1861.

Nall, R., 2020. Prostaglandins: What They Are and Their Role in the Body. [online] Healthline. Available at: https://www.healthline.com/health/prostaglandins#complications [Accessed 27 June 2021].

Straub, R. and Schradin, C., 2016. Chronic inflammatory systemic diseases – an evolutionary trade-off between acutely beneficial but chronically harmful programs. Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health, p.eow001.

Tokushige, N., Markham, R., Russell, P. and Fraser, I., 2005. High density of small nerve fibres in the functional layer of the endometrium in women with endometriosis. Human Reproduction, 21(3), pp.782-787.

Vercellini, P., Fedele, L., Aimi, G., Pietropaolo, G., Consonni, D. and Crosignani, P., 2006. Association between endometriosis stage, lesion type, patient characteristics and severity of pelvic pain symptoms: a multivariate analysis of over 1000 patients. Human Reproduction, 22(1), pp.266-271.

Vetvicka, V. and Králíčková, M., 2015. Immunological aspects of endometriosis: a review. Ann Transl Med, 3(11), p.153.

Weinstein, B., 2005. Vessels and Nerves: Marching to the Same Tune. Cell, 120(3), pp.299-302.

[…] Pain and Disease Severity in Endometriosis: Something Doesn’t Add Up […]

[…] lesions, in turn, reducing pain 2. If you don’t know what any of that means, check out this article on the mechanisms of pain behind […]